Women rights activists in Turkey are continuing their fight against sexualized and domestic violence by males. In this video by “Karşı Mahalle/Opposite Neighborhood” women protest the non-implementation of the Istanbul Convention, which should protect women’s rights.

We insist on living! The video “Kadın cinayetlerine karşı: ‘İstanbul Sözleşmesi Yaşatır’” (“Opposing femicide: ‘The Istanbul convention lives along’”) shared by Karşı Mahalle/Opposite Neighborhood is a recording of the demonstration to protest the non-implementation of the Istanbul Convention. The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and fighting violence against women and domestic violence, commonly known as the Istanbul Convention, entered into force in 2014 and requires the states parties to this treaty of the Council of Europe to “take the necessary parliamentary and other measures to exercise due diligence to prevent, investigate, punish and provide reparation for” violence against women. Turkey is considering its withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention, following protests against domestic violence in the wake of the killing of Pinar Gultekin in July and a general increase in femicides in recent years.

However, this video is not just about the Istanbul Convention. To understand what the video is about we need to look at the day before the protests. That might also be the best way to understand the language of the video.

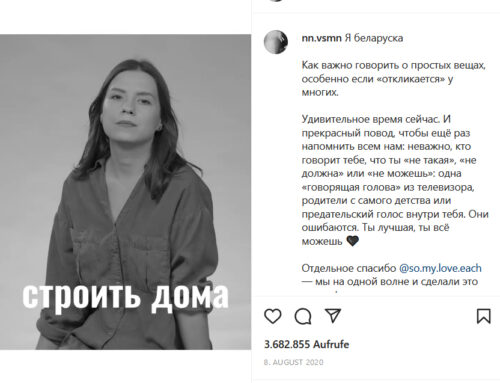

The day before the protest took place, a young university student named Pınar Gültekin was brutally murdered by her ex-boyfriend. She was a Turkish woman who disappeared on July 16, 2020. Her body was found in a rural neighborhood of the province Muğla on July 21. On July 27, a global Instagram hashtag campaign called #ChallengeAccepted was launched by a group of Turkish women in the wake of the murder of Gültekin. The hashtag received over 4.1 million posts on Instagram, including several from celebrities. The women in Turkey began sharing black-and-white photos and called it a challenge to raise awareness about femicide. The murder of Pınar Gültekin triggered emotions such as anger, sadness, and a demand for answers. In the demonstration we see in the video, women are also reaching out to their government in protest, to take responsibility for not preventing the death of Pınar Gültekin: If the Istanbul Convention had been implemented, she could still be alive.

Due to the pandemic, women demonstrated with their masks on. The masks may also have been a protective shield for feminist video activists against recognition and possible repression. According to interviews conducted with feminist video activists including Şeriban Alkış, feminist video activists normally avoid close-ups out of the same reason. In that particular situation, the women in protest wearing their masks allows the video activists to film the faces more closely. In addition, it also makes it easier to focus on the eyes that reflect the anger and pain.

Activist videos create their own feminist language. That’s what we can see, when we examine the examples in Turkey. Here, a specific language is forming: The images were taken from inside the demonstration, and the positioning of the camera tries to establish an equal point of view between itself and the subjects by not using an elevated perspective and total shots.

Şeriban Alkış, who made the video, underlined that it is especially important to make eye contact with women while shooting. Because a video activist is different from a journalist. The video activist is at the center of the protest and does not approach this process objectively. She wants to be seen and known where she is shooting from.

In my interview with activist Şeriban Alkış, who shot this video, she said that she could easily tell if a video was shot by a woman or a man. She explained this by sharing her own experience, telling how she shoots the videos by participating in them and by trying to include each and every female voice in the protest and hence, in the video. At the beginning of the video, we encounter a lot of women with different physical attributes. This is also not a shooting technique that is used in women’s video activism quite commonly these days, and if so, it depends on what period and under which circumstances the video was shot in. Therefore, we need to understand the spirit of that moment:

“We can be very different women, but there’s only one thing we want here,” says activist videographer Şeriban. “To show that we are one voice. Shout out our human rights, our desire to live together.” The murder of Pınar Gültekin led women to form a singular voice despite all their differences. A lot of women have internalized the situation by saying that ‘we are all Pınar’ in their posts shared after her death. The solidaric internalization and the commonalty of their need for collective resistance is also the reason why we see the montage of close-up images of the differing women’s faces at the beginning of this video.

Perhaps the main purpose of the video is to be able to convey this feeling to other women who were not there protesting in the streets, connecting different times and spaces. As women are so different from each other, their reactions to the underlying causes of the protest shown are also quite different. Some are angry, some are sad, some are shouting slogans some are not. “No matter how much we have suffered, we do not fill these squares to drain our emotions.” the video activist recounts. She hopes that the collective happening of the protest could be revealing for the women participating, but also, that the feelings of revelation and togetherness could be shared by those who could not be there protesting. ”I didn’t just use the music and the eyes to say we had a word”, she says. “I wanted to show how crowded this protest is, even though I actually avoid general shots, because it needs to be known how many of us there are and that we are not alone” she adds. As impressive as the music is, the video gives priority to the female voice as women shout slogans. Recordings of banners and slogans follow one after another in the montage. The prioritization of the voices shouting refers to the unsettling fact, that social life of women, which is forcefully reduced to the basic right of “We want to live,” can only be equated with the empowering fact that a woman publicly hears her voice more.

To frame the visual grammar of the presented video, we can list some central features of similar activist videos shot by feminist women:

The exemplifying videos from Turkey try to feature various slogans women shout during the protests. The order of montage and narration is not fixed to the linear development of an actual beginning or an end. Hence, the common concept of storytelling here is more fractured, associative, and circulative. It has a strong affiliation to the perception of live itself – as an everlasting process. So, it disturbingly resembles the cause it represents: Women’s struggle is not new, Women’s struggle is not over. The videos may start and come to an end, but their cause is going on.

To widen the representation of this ongoing struggle for equality, righteous recognition, societal participation and against patriarchal violence, the reproduced images of women cannot be reduced to external attributes. Moreover, feminist activist videos usually do not concentrate on the sole story of an outstanding female figure to identify with. Because by creating an identification with a single woman and the narrational possibility of an individual catharsis as a substitutive act, either blocks the right perspective on the collectivity of women’s struggle, or it gives the wrong impression of an uplifting end to these struggles.

Therefore, these videos are an effort to a feminist visual language: All kinds of fictional elements that would suppress the individual and collective voices of women are eliminated in the videos.

Women need killjoy habits, as Sarah Ahmed suggests in her book Living a Feminist Life. Maybe the presented videos could be a new language and new expressions for the women in Turkey, who suffered the violence that Ahmed mentioned in her book.

Aslı Kotaman